Help That Child, Don't Condemn Them

Dyslexia is a type of learning disability. Before diagnosis, many children with dyslexia are poorly understood. Since dyslexia has nothing to do with a person's intelligence, parents of children with dyslexia are often perplexed when their child does poorly in school or struggles to read a simple book. Is the child lazy? Inattentive? Not as smart as he or she seems?

If your child has dyslexia, you have likely asked yourself these questions as you watched your child struggle to keep up with classmates. You may have also observed your child's frustration as his or her friends gain skills that are difficult for children with dyslexia to master. The good news is that today we know more than ever before about the condition and about ways to help children with dyslexia. You can make sure your child gets the help that's needed.

What Is Dyslexia?

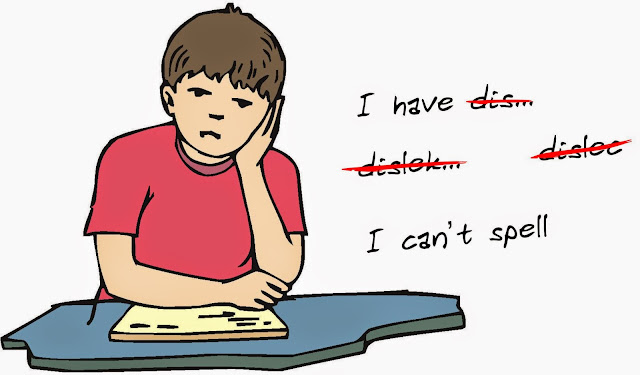

Children with dyslexia have problems processing the information they see when looking at a word. Often a dyslexic child will have trouble connecting the sound made by a specific letter or deciphering the sounds of all the letters together that form a word. Given these challenges, children with dyslexia often also have trouble with basic skills like writing, spelling, speaking, and math.

Most dyslexics will exhibit about 10 of the following traits and behaviors. These characteristics can vary from day-to-day or minute-to-minute. The most consistent thing about dyslexics is their inconsistency.

General

Vision, Reading, and Spelling

Hearing and Speech

Writing and Motor Skills

Math and Time Management

Memory and Cognition

Behavior, Health, Development and Personality

Researchers have found that dyslexia is caused by a difference in the way the dyslexic brain processes information. Experts do not know precisely what causes dyslexia, but several recent studies now indicate that genetics plays a major role. If you or your partner has dyslexia, you are more likely to have children with dyslexia. Over the next few decades, we are likely to learn much more about dyslexia and how to treat it.

Complications of Dyslexia

Children with dyslexia are at serious risk of developing emotional problems, not because of the condition itself, but because of the daily frustration and sense of failure they meet in the school environment. One study of children with dyslexia found that most of the children observed were well adjusted in preschool. But they began to develop emotional problems during their early years in school, when their reading issues began to surface.

If children with dyslexia are not identified, they are likely to begin to fail in school, and may act out, or stop trying altogether. Teachers and parents may assume that these children are simply not trying and even punish them. The child may begin to internalize the message that he or she is stupid or bad. This can become a fixed part of his or her identity, undermining self-confidence. It is not surprising, then, that children with dyslexia are at higher risk for behavior problems and depression.

Fortunately, dyslexia is now far more likely to be identified than it was in the past, when the condition was not well understood. Today, if a child has trouble reading in the early grades, parents and teachers are likely to detect the problem and provide help for the child. There are many resources now available to children with dyslexia and other learning disabilities.

How to Help Children with Dyslexia

There is no cure for dyslexia. But early intervention can give children with dyslexia the encouragement and tools they need to manage in school and compensate for their disability. If you suspect that your child has dyslexia or another learning disability, talk with your pediatrician as soon as possible. Your doctor can rule out any physical issues such as vision problems in your child. They may then refer you to a learning specialist, educational psychologist, or speech therapist. The first step will be to have your child evaluated so you can take the appropriate steps at school and at home.

Most children with dyslexia can learn to read, and many can remain in a regular classroom, but they will need help to do so. Usually, learning specialists use a variety of techniques to work with children with dyslexia on an ongoing basis. Under the Americans with Disabilities Act, children with dyslexia are allowed special accommodations in the classroom, such as additional time for tests and other types of support.

Tips for Parents of Children with Dyslexia

As parents, there are many things you can do to help a child with dyslexia:

If your child has dyslexia, you have likely asked yourself these questions as you watched your child struggle to keep up with classmates. You may have also observed your child's frustration as his or her friends gain skills that are difficult for children with dyslexia to master. The good news is that today we know more than ever before about the condition and about ways to help children with dyslexia. You can make sure your child gets the help that's needed.

What Is Dyslexia?

Children with dyslexia have problems processing the information they see when looking at a word. Often a dyslexic child will have trouble connecting the sound made by a specific letter or deciphering the sounds of all the letters together that form a word. Given these challenges, children with dyslexia often also have trouble with basic skills like writing, spelling, speaking, and math.

Most dyslexics will exhibit about 10 of the following traits and behaviors. These characteristics can vary from day-to-day or minute-to-minute. The most consistent thing about dyslexics is their inconsistency.

General

- Appears bright, highly intelligent, and articulate but unable to read, write, or spell at grade level.

- Labelled lazy, dumb, careless, immature, "not trying hard enough," or "behavior problem."

- Isn't "behind enough" or "bad enough" to be helped in the school setting.

- High in IQ, yet may not test well academically; tests well orally, but not written.

- Feels dumb; has poor self-esteem; hides or covers up weaknesses with ingenious compensatory strategies; easily frustrated and emotional about school reading or testing.

- Talented in art, drama, music, sports, mechanics, story-telling, sales, business, designing, building, or engineering.

- Seems to "Zone out" or daydream often; gets lost easily or loses track of time.

- Difficulty sustaining attention; seems "hyper" or "daydreamer."

- Learns best through hands-on experience, demonstrations, experimentation, observation, and visual aids.

Vision, Reading, and Spelling

- Complains of dizziness, headaches or stomach aches while reading.

- Confused by letters, numbers, words, sequences, or verbal explanations.

- Reading or writing shows repetitions, additions, transpositions, omissions, substitutions, and reversals in letters, numbers and/or words.

- Complains of feeling or seeing non-existent movement while reading, writing, or copying.

- Seems to have difficulty with vision, yet eye exams don't reveal a problem.

- Extremely keen sighted and observant, or lacks depth perception and peripheral vision.

- Reads and rereads with little comprehension.

- Spells phonetically and inconsistently.

Hearing and Speech

- Has extended hearing; hears things not said or apparent to others; easily distracted by sounds.

- Difficulty putting thoughts into words; speaks in halting phrases; leaves sentences incomplete; stutters under stress; mispronounces long words, or transposes phrases, words, and syllables when speaking.

Writing and Motor Skills

- Trouble with writing or copying; pencil grip is unusual; handwriting varies or is illegible.

- Clumsy, uncoordinated, poor at ball or team sports; difficulties with fine and/or gross motor skills and tasks; prone to motion-sickness.

- Can be ambidextrous, and often confuses left/right, over/under.

- Dyslexic children and adults can become avid and enthusiastic readers when given learning tools that fit their creative learning style.

Math and Time Management

- Has difficulty telling time, managing time, learning sequenced information or tasks, or being on time.

- Computing math shows dependence on finger counting and other tricks; knows answers, but can't do it on paper.

- Can count, but has difficulty counting objects and dealing with money.

- Can do arithmetic, but fails word problems; cannot grasp algebra or higher math.

Memory and Cognition

- Excellent long-term memory for experiences, locations, and faces.

- Poor memory for sequences, facts and information that has not been experienced.

- Thinks primarily with images and feeling, not sounds or words (little internal dialogue).

Behavior, Health, Development and Personality

- Extremely disorderly or compulsively orderly.

- Can be class clown, trouble-maker, or too quiet.

- Had unusually early or late developmental stages (talking, crawling, walking, tying shoes).

- Prone to ear infections; sensitive to foods, additives, and chemical products.

- Can be an extra deep or light sleeper; bedwetting beyond appropriate age.

- Unusually high or low tolerance for pain.

- Strong sense of justice; emotionally sensitive; strives for perfection.

- Mistakes and symptoms increase dramatically with confusion, time pressure, emotional stress, or poor health.

Causes of Dyslexia

Researchers have found that dyslexia is caused by a difference in the way the dyslexic brain processes information. Experts do not know precisely what causes dyslexia, but several recent studies now indicate that genetics plays a major role. If you or your partner has dyslexia, you are more likely to have children with dyslexia. Over the next few decades, we are likely to learn much more about dyslexia and how to treat it.

Complications of Dyslexia

Children with dyslexia are at serious risk of developing emotional problems, not because of the condition itself, but because of the daily frustration and sense of failure they meet in the school environment. One study of children with dyslexia found that most of the children observed were well adjusted in preschool. But they began to develop emotional problems during their early years in school, when their reading issues began to surface.

If children with dyslexia are not identified, they are likely to begin to fail in school, and may act out, or stop trying altogether. Teachers and parents may assume that these children are simply not trying and even punish them. The child may begin to internalize the message that he or she is stupid or bad. This can become a fixed part of his or her identity, undermining self-confidence. It is not surprising, then, that children with dyslexia are at higher risk for behavior problems and depression.

Fortunately, dyslexia is now far more likely to be identified than it was in the past, when the condition was not well understood. Today, if a child has trouble reading in the early grades, parents and teachers are likely to detect the problem and provide help for the child. There are many resources now available to children with dyslexia and other learning disabilities.

How to Help Children with Dyslexia

There is no cure for dyslexia. But early intervention can give children with dyslexia the encouragement and tools they need to manage in school and compensate for their disability. If you suspect that your child has dyslexia or another learning disability, talk with your pediatrician as soon as possible. Your doctor can rule out any physical issues such as vision problems in your child. They may then refer you to a learning specialist, educational psychologist, or speech therapist. The first step will be to have your child evaluated so you can take the appropriate steps at school and at home.

Most children with dyslexia can learn to read, and many can remain in a regular classroom, but they will need help to do so. Usually, learning specialists use a variety of techniques to work with children with dyslexia on an ongoing basis. Under the Americans with Disabilities Act, children with dyslexia are allowed special accommodations in the classroom, such as additional time for tests and other types of support.

Tips for Parents of Children with Dyslexia

As parents, there are many things you can do to help a child with dyslexia:

- Educate yourself. Learn all you can about dyslexia treatments, and keep up with the latest research. Seek out other parents of children with dyslexia. They may be an excellent source of information and support.

- Make sure your child is getting the help he or she needs. See that your child is evaluated and that he or she is getting the right sort of intervention and accommodations at school. Check in regularly with your child's teacher and learning specialists. Don't hesitate to intervene if your child doesn't seem to be thriving, or seems particularly frustrated or discouraged.

- Read to your child often. Encourage him or her to read to the best of his or her ability.

- Provide homework support. Make sure your child has a quiet place to study, and that he or she has plenty of time to complete homework. Try to be patient and to create a relaxed, stress-free environment at homework time. Look into tutoring. You may get help through free or low-cost community agencies. If you can afford it, private tutoring is also an option.

- Encourage your child to pursue activities he or she enjoys. Art, theater, sports, and other non-academic activities all provide positive outlets for children with dyslexia as well as the opportunity to excel.

- Give your child lots of positive feedback and encouragement. No matter how well the teacher and school work with your child, he or she may face daily reminders about being different from the other children in his or her class. Do what you can to identify and praise strengths and accomplishments.

- Get help if your child shows signs of emotional distress. Every child has occasional low points, but if your child seems particularly angry, troubled, or depressed, get professional help. Your pediatrician can refer you to a counselor or therapist.

Credits: Dyslexia.com, WebMD, Google images

Comments

Post a Comment